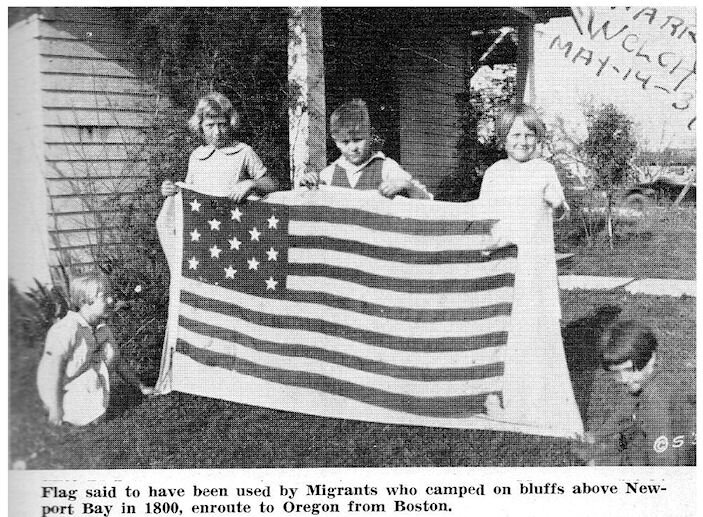

— from Samuel Meyers, 50 Golden Years, A History of the City of Newport Beach (1957)

Orange County’s 13-Star Flag – Who’s Hoaxing Who?

In 1938, a remarkable story appeared in the Los Angeles Times:

“Is there a “blind spot” in California history?

“Did the first American flag fly in what is now Orange County years before the date accepted by historical authorities?

“Has the story of the original Stars and Stripes in the Golden State been hidden for more than a century?

The article goes on to summarize the story of “a longtime resident of Southern California, who actually produces the 13-starred flag in proof of the amazing story as it was related to him.”

Let me give you a summary of that summary:

It begins with a “mystery voyage” from Boston, “sometime in the late 1790s” or the first decade of the 1800s. (Another account says it was in 1797.) A group of New England families set sail for South America. “While at sea one of the party died, and the women folks grew disheartened and wanted to give up the voyage and return, but the more adventurous ones talked them into keeping on.”

They had planned to bury the deceased passenger in Patagonia, but as they drew close to the shore, “people were seen gathering on the beach, and, not knowing whether they were civilized or savages,” the party continued on, burying the body at sea.

After rounding Cape Horn, the ship sailed on for “many thousands of miles without touching the coast.” In need of fresh water, they noticed the “clear blue stream sparkling in the sun” of the Santa Ana River, and the passengers begged the captain to stop. Turning the ship around, they came back down the coast and anchored somewhere between where the piers now stand at Newport and Balboa. The passengers were so glad to be back on land they slept on the sand that night.

The next morning, they set up tents and raised an American flag one of the families had brought with them.

Exploring by land a little further down the coast, they discovered the mouth of Newport Bay, and the captain took the ship in with the tide and anchored in the bay. Later the crew “cut a way through the tule” to move further up the bay. Climbing the bluffs beyond, “they found no trace of habitation or of Indians,” but they did find a “large springs of good fresh water” at the foot of the bluffs at the mouth of the Back Bay (below today’s Castaways Park).

There the colonists camped for the winter. The men explored the mountains, “saw the big trees … but found no good field for hunting and trapping.” They did not seem to encounter any other people, Indian or Spanish.

“The climate was mild and the women wanted to settle there permanently, but the captain and the hunters and trappers were dissatisfied and wanted to push on to Oregon. Ground was broken for gardens and fields, but in the end, when the spring had come, the majority were willing to go north and the little winter colony … was abandoned.”

The whole party sailed on to Oregon, “where the men hunted and trapped with great success.” But one winter there set them thinking of the mild winter weather back at Newport Beach.

The next spring, the ship set sail for the United States where they planned to sell their furs and buy what was needed to settle permanently on the West Coast. On the way south, four of the colonists decided to wait at their Newport camp – a married couple and two other men. The woman was pregnant and did not want to risk the voyage. They expected the ship to return that fall.

This time they made contact with some of the Spanish rancheros who lived further up the Santa Ana River. They traded seeds and gardening tools with them. When fall came, they climbed the bluffs every day to look for the ship – but it never came. They sustained themselves by farming, fishing, gathering abalones, and a little hunting.

The couple’s baby boy was born that first year. He lived to be 21, then died there at their camp. They buried him on the bluff, where they had so often stood looking for the ship that never returned.

Not long after that a ship was sighted, and to their surprise it put into the bay looking for water. Tired of waiting, the two men left with the ship, leaving the couple behind. The might have stayed there the rest of their lives, but one day when the husband was out hunting for abalones near the mouth of the bay, a sudden squall came up and he was never seen again.

Discouraged and alone, the woman moved up the river to the Yorba settlement at Olive, where she lived for many years. They told her it would be best if she kept her American flag hidden away, “as it was not the flag of this country, but of a foreign state, and might cause … trouble.”

When the first American settlers arrived years later, the woman found work as a housekeeper in the new towns. In the 1890s, she was working in a fine home in Santa Ana.

In 1899, the woman (“at that time well past the century mark”) gave the flag to Bert Stambaugh of Santa Ana. She was friends with his mother, and came to visit many times. The last time he saw her was in 1904 or 1905, sitting in a buggy downtown. He tried to speak to her, but she no longer recognized him. He could not say when or where she died, or even remember her name.

The name of this survivor and the exact date of the voyage “are the only missing links in the otherwise clear-cut story.”

As early as 1925, Mr. Stambaugh was showing off his flag around Orange County and it flew over several patriotic celebrations. According to the 1938 L.A. Times article:

“The flag, a 13-star banner of the earliest Stars and Stripes pattern – the stars arranged in vertical rows of three and two – has been pronounced an authentic original by officials of the Navy Department, and its texture has been declared of an earlier date than the ‘Betsy Ross’ flag by a national magazine investigation three years ago.”

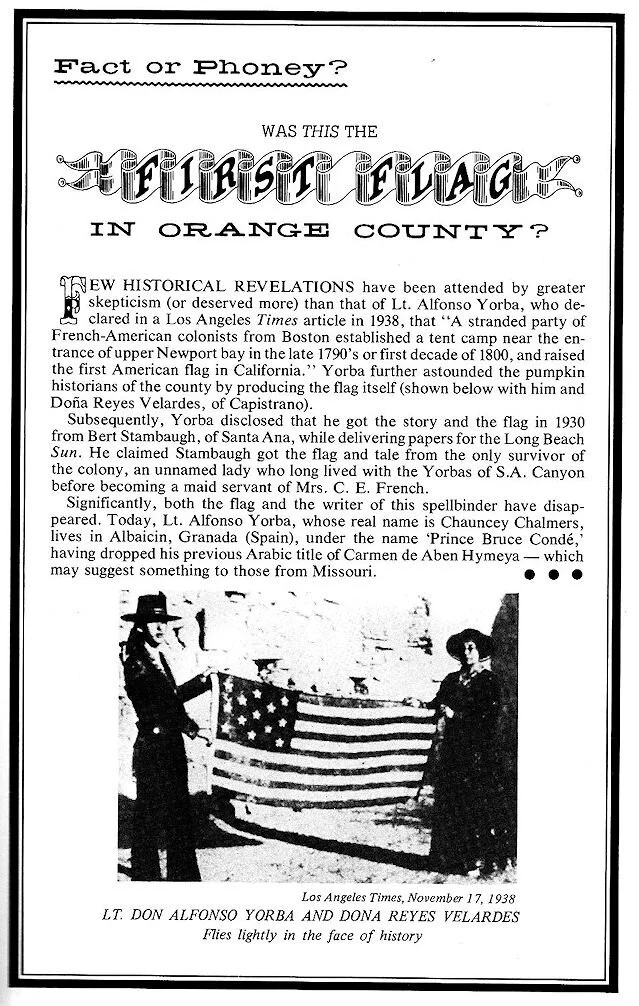

The Times article was written by Lt. Alfonso Yorba, who got the story from Stambaugh. Yorba claimed the tale was also “verified” by one of the great-grandsons of the Yorba family.

Well, that’s the story of the first American flag in California. Now what are we to make of it?

Let’s take a closer look at Stambaugh’s story and Yorba’s 1938 article. To accept it, we apparently have to believe that people could sail all the way from Patagonia to Newport Beach (thousands of miles) without stopping for water or supplies. We also have to believe that a woman old enough to have a child born around 1800 could still be alive in 1904 – at, what? A hundred and twenty five?

I might add, too, that no one in the first half of the 19th century could sail a ship into Newport Bay. The bay was too shallow, the surf and sandbars at the mouth were too treacherous; even when commercial shipping began in 1870, they used shallow draft little steamers and lost several men trying to bring them through the surf into the bay.

(There are a couple of other historical clinkers in Yorba’s article. Some of them are minor, but he should have known better.)

Taking just those three points – a 10,000-mile non-stop voyage, a woman living to be 125, and anyone sailing into Newport Bay in 1800 – I feel safe in saying that this story is a fraud.

The first question this raises is: so who was hoaxing whom? Did some old woman pass this story off on Bert Stambaugh? Was Stambaugh telling tales?

Alfonso Yorba did genuinely seem to believe it, pushed Stambaugh for more details, and searched for other old Santa Ana residents to confirm the story. But Yorba’s own story contains more than a little that’s unbelievable.

He was actually born Bruce Chalmers, only later adopting the Yorba name (though he insisted he was a descendant). His historical articles from the 1930s sometimes contain more old-timer tales than researched history. And his later life – perhaps including a stint as a spy and certainly including (I kid you not) the role of Postmaster General for one of the revolutionary governments in Yemen – ended with him claiming royal descent, and living in Tangiers as a man without a county.

None of this makes him a particularly creditable witness.

But then there is that 13-star flag. We know it existed, it was photographed several times. In fact, it may still exist.

Jim Sleeper’s take on the flag story from his second Orange County Almanac of Historical Oddities (1974).

It’s been a couple years now, but I was once contacted by a man who claimed to be the current owner. He had some story about how he had acquired it (through a bankruptcy, or debt, or a poker game – I freely admit I have forgotten which – anyway, it was in a storage locker somewhere).

He was looking for someone to authenticate it. Unfortunately, he wasn’t willing to show it to anyone. He was mostly interested in matching up early photos of the Stambaugh-Yorba flag to prove he had the same one.

I was disappointed to explain to him that if he couldn’t show it to me, I couldn’t “authenticate” anything. And there our conversation ended.

If I could see it, I think I know what I would find. Jim Sleeper, the great old Orange County historian, thought the same thing (or something like it).

The materials, the manufacture, I’m sure would be wrong – wrong fabric, wrong stitching. That’s because it was probably made sometime between about 1860 and 1900 – as a Naval flag.

The proportions and the pattern of the stars are the giveaway. These flags were designed to fly off smaller boats, so they only included 13 stars arranged in that distinctive 3-2-3-2-3 pattern (known to the vellixologists as a Hopkinson pattern – a whole other rabbit hole I have no intention of going down.)

(I assume that at least everyone who’s watched “The Big Bang Theory” now knows that a vellixologist is a flag expert.)

I am not a flag expert. But 40-plus years as a historian has taught me that when a story seems too good to be true it usually is.

I don’t know who flew the first American flag in California, or what became of it – but it wasn’t this one.

Postscript

I originally wrote this article in 2018 as a talk for a historical group in Los Angeles. It was almost a year later that I discovered – quite by accident – that there was a thick file on the supposed 1790s flag in the records of the Newport Beach Chamber of Commerce (now held by the Sherman Library in Corona del Mar). The file begins in 1925, the same year the story seems to have first hit the papers. There are numerous letters from Bert Stambaugh over the next 15 years, and usually he seems worked up about something. At times he seems almost possessed by the idea that his story was being purposely denounced by the powers that be. His story, at least, is consistent, and he truly seems to have believed it. He says repeatedly that the Yorba article was good, as far as it went, but many things were left out (he never quite specifies what). “The Yorba article is true and correct absolutely free from fancy fables.”

Yorba encouraged him to find a place to permanently display the flag, “provided it is accepted and exhibited according to the [1938] Times article and without any other data which we have not passed on or approved,” he wrote to Stambaugh in 1939.

Stambaugh does add a few more details. He says the old woman was well known among the cycling crowd around 1900 as “the oldest woman bicycle rider in and around Santa Ana and Orange. She was some where around 80 years old and still spry – on her bike…. A number of people at Santa Ana remember this old woman. But none of us can remember her name.” But in a letter 14 years later he calls her “Old Rachel,” and seems to call the ship the Boston Harbor. He estimated her age at about 15-16 years old when they arrived on the coast. The flag, he said, “was made out of wool on a spinning wheel. It has been repaired several times.”

Stambaugh was always looking for someone to back him in his claim – the chamber of commerce, the county publicity department, the Orange County Historical Society, Bowers Museum – anybody. “You may say for me,” he wrote in 1939, “that the truth belongs to no man or any select set. To side track a true story of historical merit is dead wrong…. The way is open for all of them to peddle their own fish, if they wish to brush aside the Times-Yorba story.”

The letters continue through 1940, and grow more rambling and even a little paranoid as Stambaugh begins to equate people’s disbelief in the flag story with personal attacks on himself. But his claim never wavers.

Most interesting to me, though, is a letter to the chamber of commerce from the first great Orange County historian, Terry Stephenson where I find he had reached some of the same conclusions as me 80 years before:

Santa Ana, California.

December 17, 1938.

Mr. Harry Welch,

Chamber of Commerce,

Bx. 118, Balboa, California.

Dear Harry – I have known about the flag story for a number of years. I have had considerable correspondence about it with Bert Stambaugh and have discussed the matter with Alfonso Yorba.

I told Stambaugh and Yorba – that is, I wrote it to Stambaugh and said it to Yorba – that there is absolutely nothing historical about the story. That is, there is nothing that any person with training in historical investigation could tie to. There is nothing that I have ever read that indicates any truth in the story. I have talked to many men who knew the area in the 1870-period – Robert McFadden, James McFadden, John Cubbon, Capt. Kelly, McMillian, Tibbetts of Riverside, who was there in the ‘60’s – and none of them ever said a word that indicated any previous occupation…..

Hazy as the story is, certain things must have been so, if the story was true. First, the woman must have been 120 years old when Stambaugh got the story, and she must have been 125 when he saw her last. Second, the family should have been recorded in the various census reports, both Mexican and American. No names that possibly could have belonged to the family appear in a census taken about 100 years ago. Third, anybody with a story like that should have attracted the attention of somebody beside Bert Stambaugh.

Bert ran a bicycle store here at the time he says he got the story. His letters ramble, he brushes aside all efforts to get at facts.

I am interested purely from the historian’s point of view. I have no desire to create unfounded tradition. William McPherson, now president of the Orange County Historical Society, agrees with me that this Stambaugh story is not historical. You, however, need not be bound by any such a fence as surrounds those of us who think we are bound by the facts. Perhaps you could grab the yarn, and make it go, just as San Juan Capistrano has made the swallow story go over. I heard Frank Miller of the Mission Inn once say that if you built an adobe shrine beside the road, the public would soon have stories built about it, enough of them to make the shrine famous.

I’ll be mighty glad to talk it over with you any time.

Sincerely,

Terry Stephenson.

— And there I leave it.

But all and all – I’d still like to see that flag someday.

A Naval flag from around 1900 – what do you think? Here is an auction report on one of these flags.