Walter and Esther Mills outside their Trabuco Trading Post, circa 1955 (courtesy the Orange County Archives).

Trabuco Oaks – A Canyon Community

Even as Orange County has grown, the little communities scattered through the canyons of the Santa Ana Mountains have managed to retain their rural charm. Trabuco Oaks is a prime example.

The first American settlers began arriving in the mountains in the 1860s. This was one of the few areas in Orange County open to homesteading. In the Trabuco country, the Southern Pacific railroad also owned alternating sections in a checkerboard pattern, part of the land given to them by the government as a subsidy to help the SP pay to build new railroad lines in California. This left the settlers with two choices: buy land from the railroad, or homestead it. Buying railroad land cost about $2.50 an acre in the early days – a substantial investment when only large parcels were available. Homesteading, on the other hand, would cost them five years of their lives and the work of transforming raw land into a functioning ranch. Still, that was the route many settlers chose.

Albert Hamilton, Labon Weakly, James Hickey, and N.T. (“Tule”) Wood were early settlers in the Trabuco Oaks area. Hickey Canyon, where Trabuco Oaks is located, was originally called Weakly Canyon, while Hickey himself kept bees in what is now Rose Canyon.

Edward Rowell came in 1875 and bought 160 acres from the railroad on the west side of Hickey Canyon at the first fork. At one point he also owned what was later the “Holy Jim” Smith place in the canyon that now bears his name. Rowell’s sons, George and Frank, also became bee ranchers. Much of today’s “downtown” Trabuco Oaks is on the old Rowell place.

The Adkinson family learned the hard way that between ranchos and railroads there was little land left for homesteaders in Orange County. Family patriarch Jesse Adkinson had originally tried settling on what he hoped was public land between the ranchos Santiago de Santa Ana and Las Bolsas, in today’s Fountain Valley area, but the courts ruled otherwise. So he came up to the Trabuco country in 1883 and settled in the Trabuco Oaks area where he lived until his death in 1926. His sons, Jesse Jr. and W.E. (Ed) Adkinson, were prominent canyon residents for decades.

Of course, little of the Trabuco country could really be considered farmland, and the heavy brush on the hillsides left little feed for grazing stock, so the earliest settlers also turned to a different crop and a very different sort of ranching – bee ranching.

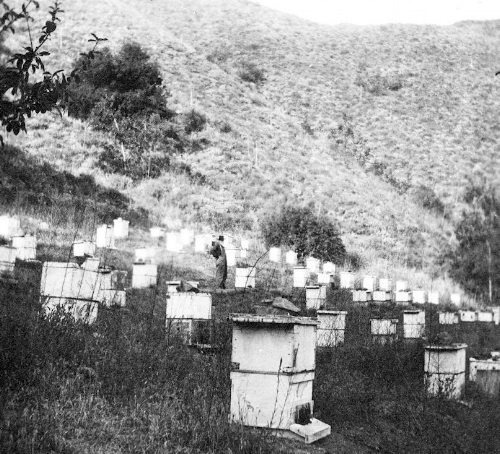

Beekeeping was one of the most important industries in the Santa Ana Mountains in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The bees fed on (and pollinated) every flowering plant that grew in the hills. Spring and early summer were the best seasons, but there was always some pollen available. The colonies (each with their queen) lived in beehives or “stands” set out by the bee ranchers. The stands held removable panels where the bees would build their honeycombs. These were removed from time to time while the bees were out foraging, one end of the waxy comb sliced open with a hot knife and the panel spun inside a metal cylinder to extract the honey. With a little care and a little hurry, the frames were back in the hive by the time the bees returned, ready to refill them. The honey was stored in drums, some holding as much as 1,500 pounds. Two men working together could fill one in a day during the height of the harvest, with 180 pounds a year per hive being considered a good yield. The honey crop for Southern California was estimated at three million pounds in the early 1880s. The returns were low (only 4-5¢ a pound), but it was a dependable cash crop for many canyon homesteaders.

A bee ranch in the Santa Ana Mountains, 1914 (courtesy the Orange Public Library and History Center).

Even by the standards of the late 19th century, this was true pioneer living in the Trabuco country. Santa Ana and San Juan Capistrano were the closest towns of any size, and neither could muster a thousand souls in 1880. So the canyon residents learned to make their own and make do for just about everything. Water came from creeks, springs, or hand-dug wells. Supplies that couldn’t be grown on the ranches were hauled in by wagon, up over the Harris Grade from Cook’s Corner and down Live Oak to the Trabuco.

Beginning in the 1880s, Clara Mason Fox lived this pioneer life in Silverado and Aliso canyons. Nearly 50 years later in her history of El Toro she recalled:

Every farmer had cows and chickens, often hogs, and some times a few stands of bees tucked away in a corner somewhere, and often the domestic well was made to keep up the spring gardens. Every woman put up her own fruit and preserves, made her own bread and pastry. Staples – flour, sugar, coffee and tea – were the principal articles acquired from “the store.”

Clothing was plain and inexpensive, a “good dress” lasting a woman at least two years, [a] suit for a man being good for several years. Children went barefoot most of the year, if not all of it, and boys always wore overalls at home and at school, some having a suit for “dress up.”

Every member of the family had duties, the boys always doing the chores – feeding all the animals and fowl; cleaning corrals, stables and chicken houses; milking the cows, bringing in the wood, and perhaps cutting it. Most girls had to help with the housework, and sometimes with the chores also. When clothes were all made at home, washing done on a washboard and ironing by “sad irons” heated on the kitchen stove, all the bread baking and pastry making done there, mother needed assistance.

As in many places on the frontier, the first real sign that a community was developing in the canyons came in 1879, when the Trabuco School District was formed. It was the first school district in the Santa Ana Mountains. The statistics for that first year give us some idea of the community at the time. There were 58 school age children (ages 5-18), but only 19 enrolled and the average daily attendance was only eight pupils.

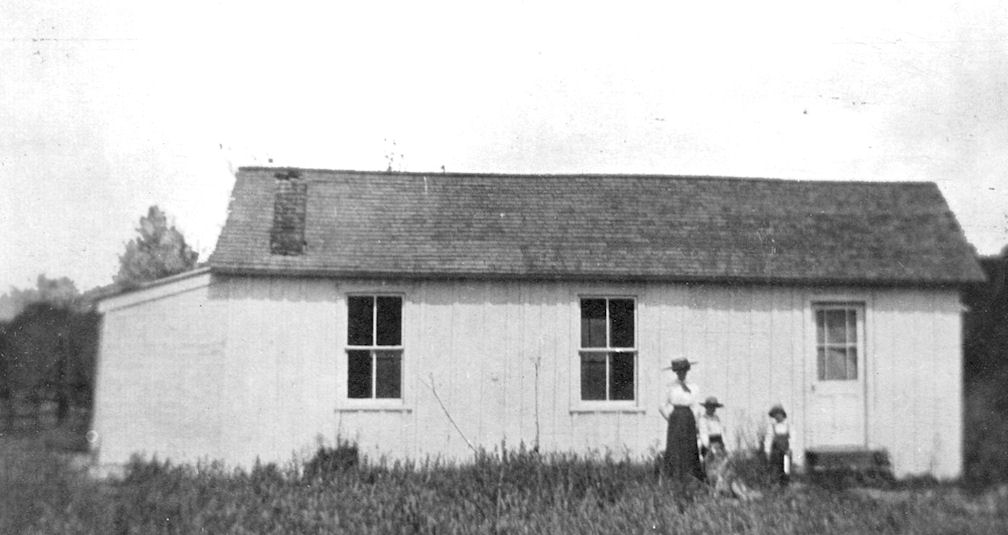

The first classes were held in a small building on the Lyons Ranch, with Minnie Joslin of Orange as the only teacher. This was a one-room school, for grades one to eight. Like most local schools of the day, it probably had benches rather than desks, with the students arranged from the youngest children in the front (closest to the teacher) to the oldest in the back. There would have been few textbooks, and almost no other teaching equipment. But there were advantages to the one-room school as well. The older students, for example, were often expected to help teach the younger ones – a positive arrangement for both young and old. For most, 8th grade graduation marked the end of their academic career – there was no high school closer than Los Angeles until 1889.

The Trabuco School moved almost every year in the early days – from the Lyons place, to the honey house on the Straw Ranch, to the Rowell house, then to another honey house on the Greenleaf Ranch. Finally, in 1888, Richard O’Neill donated three acres for a school site on behalf of the Rancho Santa Margarita Company. It was located just south of the ranch line, at the bottom of Live Oak Canyon, very near the current entrance to O’Neill Park.

When Florence Conlee Dickerson attended the Trabuco School around 1900 things were still quite primitive. Drinking water came from a nearby well, carried in a bucket back to the schoolhouse where everyone drank from the same dipper.

“During the rainy season we had a swimming pool in the creek. We made it by damming up a wide place in the stream with rocks. It was nice and clean and quite deep. The boys had the use of it one day and the girls the next. When the girls used it, Miss [Pearl] Gray [the teacher] was always there, but when the boys had it, I think they were on their own.”

Alice (Robinson) Divver taught at Trabuco from 1909-11. “I rode horseback two miles each way,” she recalled in a letter to historian Jim Sleeper, “rain or shine, nine months of the year and taught all subjects for all grades. The pupils didn’t seem to mind that they got no music instruction since I am tone deaf. We had no athletic program.” There was at least a small library in a little room in the back.

What’s more, many of the early teachers were young women just starting out in their career, and with no hotels or apartments around, most lived with one of the local families. This led to a number of marriages over the years.

The Trabuco Elementary School, circa 1910; located in what is now O'Neill Regional Park.

As the only “public building” in area, the Trabuco School soon became the center of the community. It served as a polling place for elections for more than 35 years. The Trabuco Precinct, in fact, “went solid” in the vote on the creation of Orange County in 1889, casting 13 votes in favor of the new county and none against. Trabuco’s voters were mostly Southern Democrats in those days, but party politics had nothing to do with having their own county.

The “Trabuco Literary Society” met there in 1890s and Baptist services were held in the schoolhouse as early as 1895 by the Rev. G.E. Jones. The many Southern families in the canyon probably made this a good fit, but pastors from other denominations preached there from time to time as well. And if no regular minister was available you could always have Sunday School. There were also revival meetings and even baptisms in the creek.

Even more lively were the dances held on Saturday nights, where the residents “cast off all reserve, waxed hilarious and shouted and pranced and stamped till daylight.” Everyone brought food to share, and the folks that could provided the music. “Uncle Sheelix” (Robert M. Shaw) played the fiddle, while “Professor” Walter S. Morrow and his wife performed on violin or guitar. “The dances were very lively affairs,” Anne Robinson of the Robinson Ranch recalled in her memoirs, “with the fiddlers stamping their feet, and everyone, irrespective of age, bowing and skipping and swinging at the direction of the caller, for the most of the dances were quadrilles, interspersed with two steps and waltzes.”

The Trabuco School was always one of the smallest in the county. It was further reduced in 1886, when parents along Aliso Creek secured their own school district to save their children the long trip over the hills to Trabuco. The Aliso School was located about 300 yards below Cook’s Corner on the east side of the creek. It operated until 1905.

As the 20th century began, the Trabuco country was still ‘way out in the hills.’ Cattlemen ran cattle, beekeepers tended their bees, and farmers plowed the Trabuco Mesa. There were no paved roads, no electricity, no stores, not even a post office. But as cities grew on the flatlands below, folks began to appreciate area’s rural setting more and more. Over the years, a number of small vacation and resort tracts were laid out in the Santa Ana Mountains. In the days, before freeways and easy air travel, many folks vacationed, as it were, right in their own backyard. By the 1920s, a few even decided to make the canyons their home.

Seizing the moment, in 1928 David Moulds subdivided part of the old Rowell ranch near the mouth of Hickey Canyon, just over the line from the Rancho Trabuco. There were about 270 lots along seven winding roads, most about 50-feet wide but of varying depths depending in part on the topography. Moulds laid out a water system and built a few vacation cabins and in May 1928 the tract went on the market as Trabuco Oaks, a “mountain resort” offering year-round living. A large lot was just $100, or you could rent one of Moulds’ little cabins for $5 a week.

Trabuco Oaks was slow to catch on, and the depression of the 1930s really put a damper on Judge Moulds’ plans. He died in 1932 without ever seeing his tract take off. The few buyers were mostly vacationers. But when the El Toro Marine base opened up (and especially after World War II) a number of servicemen moved their families there, and the number of year-round residents grew. By 1944 about 75 families lived in the “little community of Trabuco.”

In 1938 the area finally got a post office. The Trabuco Canyon Post Office was officially authorized on October 7th, but apparently didn’t open for another month. Ethel Glenn was the first postmaster, serving until 1947. The post office was located in a little grocery store she and her husband, Grady Glenn, had started next to their home along Trabuco Canyon Road at the turn to Rose Canyon. Beginning in the 1930s, Mrs. Glenn also served as librarian of the little county branch library there. Later it was moved across the road to the school.

The Glenn market was not the first store in the canyon. As early as 1930, Charles Herring had a “camp store” in the “little settlement” at Trabuco Oaks. But having the post office gave the Glenns a definite leg up. So when Ethel Glenn decided to retire in 1947, Oscar Huffine seized the opportunity, applying for the job of postmaster and building a new store at the bottom of Trabuco Oaks Drive. This was the start of the Trabuco Oaks store that we know today, with the post office located on the west side of the building.

But things don’t seem to have worked out the way Huffine planned, and he resigned as postmaster in 1948. Otto Ohngren took over the store and post office in 1949 and ran them both until 1952 (it was known as Otto’s Grocery in those days). The store continued to change hands, but in 1952 Esther Mills became the postmaster and held the job for the next twenty years while her husband ran the store until 1968.

The post office finally left the store in 1984 when it moved down the road to its own building. Clara Sears was postmaster then. As modern communities grew up around it, the Trabuco Canyon Post Office was assigned more and more territory, include parts of Rancho Santa Margarita, Robinson Ranch, Coto de Caza, and even Portola Hills. This has led to some confusion as press reports and real estate ads speak of homes “in” Trabuco Canyon – but true canyonites know better.

In the 1950s and ‘60s the store was known as the Trabuco Trading Post. They had a gas station, too, until the oil crisis of 1979. In the ‘80s it was the Emory Store. It has passed through several hands since then and today is known as the Trabuco General Store.

Trabuco Oaks got its first restaurant in 1956 when Wendell and Ivy Beardslee opened Beardslee’s Chuck House Cafe along Rose Canyon Drive. The place featured burgers, fried chicken, and steaks, and offered an open air dance floor and horseback riding from the family’s adjoining stables. To help attract customers, they also kept little “zoo” out back with possums, skunks, foxes, raccoons, a monkey, and even a beer-drinking donkey.

Ivy Beardslee was a true Trabuco Oaks pioneer. She had come with her family in 1932 and her father, Henry Atsell, soon became tract agent. (He built the little stone house that still stands across the road from the store as a tract office.) Ivy lived in the canyon more than 60 years until her death in 1996. Wendell Beardslee died in 1972. The Beardslees and their daughters closed the cafe around 1969, and it briefly became a biker bar known as the Hideout. Then in 1978 Lico Miranda re-opened it as Señor Lico’s Mexican Restaurant and ran it until 2002. The Beardslee girls then reopened it as the Rose Canyon Cantina and Grill, which since 2005 has been leased to Mr. and Mrs. John Cox.

In the meantime, in 1968 the Trabuco Oaks Steakhouse opened just up the road from the Trabuco Store in what had been a “beer joint” called George’s Place. Originally it was little more than a snack bar, serving local residents and campers at O’Neill Park. Later it expanded to offer full meals. Famed for its food, its atmosphere, and its promise to cut off the ties of anyone foolish enough to wear one through the door, it remains a popular dining spot to this day.

In 1926, shortly before Trabuco Oaks was founded, the old Trabuco Elementary School had closed for lack of students, and the few remaining local children had to go over the hill to El Toro to go to school. Ironically, it was the Depression of the 1930s that gave Trabuco Canyon its own school again. So many families were camping out in the local canyons that in 1932 the El Toro District established a second school in a barn at Trabuco Oaks. It was cheaper than busing the students down to El Toro and back every day. “There are many families living in this canyon,” the Santa Ana Register reported, “… although not a permanent structure exists in the mushroom village. There are 50 or more children.”

Over the next few years the El Toro district wavered, sometimes holding classes in Trabuco and other years busing the kids over the hill. So local parents began lobbying for a separate school district of their own again. At first the state resisted, but in January 1942 both the state and county agreed to re-establish the Trabuco School District. (The fact that County Superintendent of Schools Ray Adkinson was a Trabuco grad probably didn’t hurt.)

The revived Trabuco School District started classes that fall in the “fireman’s quarters” (presumably at the U.S. Forest Service station where the Live Oak Canyon Stables are now located, with about 15 pupils. Phyllis Wannamaker was the teacher the first few years, and just like some of her predecessors ended up marrying one of the local ranchers – George Harris. The school later moved to a shed on the Robinson Ranch, then that building was moved down into the canyon. Finally in 1946 the Rancho Mission Viejo Co. donated 4.6 acres on a former CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps) labor camp site – the home of Trabuco Elementary School ever since.

The school remained small for many years. The average daily attendance was just 24 students in 1955, but that was finally enough to add a second teacher. A new, two-room school was built about that time, and served for more than a decade.

In 1973, Trabuco became part of the new Saddleback Valley Unified School District. There have been several calls to close the school over the years (especially after development began on the Trabuco Mesa), but Trabuco Elementary School has survived, and remains Orange County’s last rural school.

Like the school district, the Trabuco Election Precinct was also usually one of the smallest in Orange County (just 25 registered voters in 1904). In the 1930s it was still the smallest precinct in the county. Yet it managed to supply three of the county’s most prominent elected officials in the early days and kept them in office for years – and all of them were Democrats to boot!

Local elections usually didn’t stir up much trouble. The Trabuco Elementary School District was the only local elected body, and in the 1940s there weren’t even any declared candidates for most school board elections – every trustee was elected as a write-in candidate. The biggest fuss was in 1948-49, when the district tried twice to pass a bond act to build a new schoolhouse. (The 1949 Grand Jury said, “Conditions at this school are primitive…. It seems a waste of the taxpayers’ money to keep this school open.”) Both bonds failed, and district clerk Wendell Beardslee was recalled by a vote of 34 to 22. Donald Rook was elected in his place and a new school was finally built half a dozen years later.

Politicians were prominent, but perhaps the most important public officials in the Trabuco country were the local firefighters. County, state, and federal crews all worked closely together, often even sharing facilities. Beginning in 1936, the U.S. Forest Service and the California Division of Forestry had a shared station at the corner of Live Oak and Trabuco canyons, where the Live Oak Canyon stables are today. By 1950 the state forestry station had moved to its current location along Trabuco Canyon Road. That same year, with help from the county, the local volunteer fire department built their own adobe brick fire station next door. Joe Scherman looked after both stations as State Forestry Ranger and County Fire Warden.

The new Trabuco volunteer fire station building, 1950 (courtesy the Orange County Archives).

One of the first buyers in the Trabuco Oaks tract was Fred Schwendeman, a former Irvine Ranch employee and one of the original city councilmen in Tustin, where he ran a concrete irrigation pipe business for many years. He bought a lot in 1930 and built a vacation cabin the next year. Later he built a larger, Tudor-style home (still standing) and moved to the canyon year-round. His son, Leonard (1918-2009), built a home in the canyon after his marriage in the early 1940s and became a fixture in the community, serving as chief of the volunteer fire department, a school board member, and a founding director of the Santa Ana Mountains Water District (now known as the Trabuco Canyon Water District) organized in 1962.

As Orange County grew up in the 1950s, Trabuco Canyon became only more inviting. O’Neill Regional Park (founded in 1948) was packed with campers and picnickers on weekends in the 1950s and ‘60s. Increasing tourism also brought more business to the area. The Live Oak Canyon Riding Stables across from the park opened around 1960 and was operated for many years by Ralph Lindsay. At one time it also boasted a miniature train, a “peewee” golf course, and go-karts.

While religious services had been held from time to time in the Trabuco country since the 1890s, it was not until about 1969 that the first church opened in the area. The non-denominational Trabuco Community Church, overlooking Live Oak Canyon is still an active congregation to this day.

Modern development finally reached Trabuco Oaks in 1985 when (to the dismay of some) work began on the Live Oak Center, a retail/office complex adjoining the post office. But even with the development of Rancho Santa Margarita up on the Trabuco Mesa, the canyon country has managed to retain much of its rural feel.