Walter Knott, circa 1960 (courtesy the Orange County Archives).

Pioneer Harvest

The Life of Walter Knott

Orange County has been home to more than its share of unique characters, but few were as unlikely as Walter Knott (1889-1981). His rags-to-riches story (as he saw it) typified the American Dream. His rise from tenant farmer to theme park founder made him nationally famous, and he used that fame to promote his vision of America.

But Walter Knott was much more than his political enemies’ caricature of a dour, old, uber-conservative farmer. He was hard-working, imaginative, and a natural-born entrepreneur. Knott’s Berry Farm stands today as a testament to his dedication and his abilities.

A great deal has been written about Walter Knott, including at least five book-length biographies. The best is Helen Kooiman’s Walter Knott, Keeper of the Flame (1973), but none of them – in my view – really do justice to Knott’s unique story. To do that would fill at least another book or two. Instead, here are a few episodes and observations from his long life that seem especially significant to me.

-o-

First the basics . . . Walter Knott was born of pioneer stock; his mother’s family arrived in Southern California by covered wagon in 1868. His father, Rev. Elgin Knott, was a Southern Methodist minister who had come to California for his health in 1880. When his first son, Walter, was born in 1889 he was preaching in Orange County. The church he preached in still stands next to the Greenville Country Church in Santa Ana. Two years later he was sent to another Orange County little community – Bolsa, the site of today’s Little Saigon neighborhood in Westminster.

But life for the Knott family was turned upside down in 1896 when Rev. Knott died of tuberculosis at age 37. His widow and two sons eventually settled in Pomona, where Walter Knott grew up. Even as a boy, he dreamed of being a farmer. He’d rent vacant lots around town to grow produce to augment his family’s income. It’s sometimes said he dropped out of high school, but in fact, California law did not require schooling beyond age 16 in those days. In 1911, he married his high school sweetheart, Cordelia (“Cordy”) Hornaday (1890-1974). He had a good job with a local cement contractor, and had just built his own home.

Success or Failure?

The approximate location of Walter Knott’s homestead near Newberry Springs — still open desert country.

But Walter Knott yearned to be a farmer. Too impatient to save up and buy his own place, Knott decided to homestead on the Mojave Desert, filing on 160 acres northeast of Newberry Springs in 1913. Life on a desert homestead was hard – especially for a city girl like Cordelia. They lived in an adobe house, planted grapevines and a few other crops, but just couldn’t get enough water. So Knott took any job he could get until he could prove up his homestead and take title to the land.

His next attempt at farming came in 1917, when a cousin pointed him toward the tiny town of Shandon in San Luis Obispo County. A cattle ranch there needed someone to grow produce to feed their employees. Knott took the job with permission to sell the excess crops. In effect, he became a tenant farmer. Cordelia pitched in as well, making homemade candy to sell. In three years, they’d gotten out of debt and made enough money to move on.

Various writers have portrayed these years differently. Some saw them as a failure, and while it’s true that Knott had failed to launch his own farm, he had shown that through hard work and determination, he could see things through, even when times were tough. It’s a lesson he would have to return to many times in the coming years.

Walter Knott showing off his corn crop, probably at Shandon, circa 1920 (courtesy the Orange County Archives).

Towards the end of 1920, another cousin approached Walter Knott with another opportunity. Jim Preston was already an experienced berry grower. Now he offered to go into partnership with his younger cousin growing berries in a place called Buena Park.

“We learn with much regret that our enterprising and industrious gardener, Walter Knott, is planning to leave for the south sometime this winter to make his home there,” the San Luis Obispo Daily Telegram reported (10-28-1920). “Shandon has been well supplied with all kinds of delicious vegetables and green goods the past year, and a great quantity was shipped to Paso Robles and other cities. It will be quite a loss to the community both from a commercial and a social viewpoint, as the Knotts were active in church and club work. They will be greatly missed.”

Just before Christmas, 1920, the family hit the road in an overloaded Model T Ford, bound for Orange County.

Knott’s Berry Place

Preston & Knott leased 20 acres south of Buena Park, and for the next seven years grew berries there. While Preston had the experience, it was clearly Walter Knott who did most of the work, living with his family in a little house just south of the farm. Along with selling to wholesalers, around 1923, Knott opened a little berry stand by the side of the road. It was a good location along Grand Avenue, a natural cut-off for tourists on their way to the beach.

Retail sales also required advertising, and Preston & Knott began buying larger and larger ads in the local newspapers. By 1927 they had added a mail order business as well, publishing their own catalogs. Walter Knott seemed to instinctively understand the value of good advertising – another trait that would help him go far.

That same year their original lease was up, and Jim Preston and Walter Knott decided to go their separate ways. Preston started his own berry farm in Norwalk, while Knott made a deal to stay on in Buena Park. He offered their landlord $1,500 an acre for ten acres. ‘It isn’t worth fifteen hundred an acre,’ the man told him, ‘and you know it.’ Yes, Knott agreed, but then he had to admit that he didn’t even have the money for a down payment. ‘Well, with nothing down,’ the owner said, ‘maybe it is worth fifteen hundred an acre.’ So that was the price, and Knott stuck to it even after land values plummeted during the depression.

“It never entered our heads that we might not succeed,” Knott later recalled. “We had all the requisites for success. We were young, well, full of ambition, had confidence in ourselves, were willing to work long hours. We had already gone broke on a desert homestead and had learned that we could go without a great many things other people thought they had to have. We had good land and enough water…, and we were going to have the finest berry farm in California, and we were willing to study, learn, and work hard and do without to get it.”

To prove he was there to stay, in 1928 Knott replaced his little roadside stand with an 80-foot stucco building, with a nursey, a berry market, and a “tea room.” Cordelia Knott had made it clear that she had no interest in running a restaurant, but agreed to sell pie, burgers, and sandwiches from her tiny “tea room.” Cooking was done in her home kitchen, out back. Chicken dinners didn’t go on the menu until 1934, when the depression forced the Knotts to look for even more sources of income. That was the same year that Walter Knott introduced the boysenberry.

Walter Knott tending the counter inside the berry market, circa 1940 (courtesy the Orange County Archives). The building, much remodeled, still stands.

Initially, Knott’s Berry Place was only open during the summer harvest season. But by 1937 the business had grown big enough to stay open year ‘round, freezing berries to meet their needs the rest of the year. Cordelia’s tea room was growing as well, with new additions on all sides.

But there was a problem. Right outside the windows was a tall concrete standpipe, a part of the farm’s irrigation system that couldn’t be easily moved. It was an eyesore, but what to do?

“When you have a difficult problem,” Knott later explained, “analyze it carefully, study out all the possible solutions, think it through as thoroughly as you can. Then, dismiss it from your mind. If you have done your homework properly, your subconscious mind will go to work for you and give you the answer without any further conscious effort of thinking about it.”

The volcano outside the Chicken Dinner Restaurant, shortly after it was completed in 1939 (courtesy the Orange County Archives).

And so it was that one day Walter Knott’s subconscious said to him the magic word: volcano. He would cover the standpipe with a pyramid of desert rock, add a steam pipe, and call it a volcano. Whether his subconscious also said, build a little devil turning a crank to run it is not recorded.

Other early attractions to amuse visitors while waiting for a table included a fluorescent rock display, a collection of antique music boxes, a rock garden, an old stage coach, and a re-creation of a fireplace from George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon.

This transitional period in the history of Knott’s Berry Place is sometimes ignored in later accounts, but it leads naturally to everything that follows. By 1940, Knott’s Berry Place already had boysenberries and chicken dinners, historic displays and curiosities, a focus on serving their customers and a healthy advertising budget.

Ghost Town Village

In 1940, Walter Knott came up with another bright idea. Why not tell the story of the pioneers crossing the continent in the form of a cyclorama? That is, a curved, painted backdrop and miniature scene in front, with music and narration. It was a common type of tourist attraction in the early 1900s. Knott had grown up on his grandmother’s covered wagon stories, and saw the frontier as an example of American drive and determination. What better story to tell?

From there, the idea grew. The cyclorama needed its own building – why not make it look like an old Western building? And why just one building – why not a whole block of Western storefronts? And so, Ghost Town Village was born.

The story has been told many times: how Knott’s crews searched out old buildings for materials (they didn’t actually move in many buildings, and most of those came from nearby cities); how the false fronts grew into real buildings, with shops and displays inside; how costumed characters roamed the streets, and Sad Eye Joe sat in his jail cell.

As Walter explained in 1942, “Every time I have the opportunity to get away for a couple of days I like to visit the ghost towns of the west for we are continually seeking materials with which to reconstruct the ghost town here at Knott’s Berry Place. By securing a building here, part of another there, an old bar in one place or something else somewhere else we add to the picture we are attempting to portray – a composite picture of the ghost towns of the west as they appeared in ‘49 and the early ‘50’s. We are not collecting museum pieces nor is it the intention to build a museum. Our thought is to collect a town but as that is impossible we try to do the next best thing – build or reconstruct a ghost town that will be authentic and show life as it was lived in the early days.”

(For more on the history of Ghost Town, click here.)

In a strange way, there was a reality to Walter Knott’s fake ghost town that most other tourist attractions lacked. The post office was an official government post office branch. Businesses like the grist mill actually ground grains on the old equipment for sale. Knott even considered registering his railroad as a common carrier. And his town also included a broader range of community life, including a school and a church (both lacking, for example, in Walt Disney’s re-creation of small town American life at the entrance to his theme park), and even (to Cordelia’s disgust) a brothel.

Perhaps predictably, Walter Knott’s portray of the American frontier has been called into question in recent years, with certain writers arguing that his image of the rugged individualism that built the West is as false as his artificially-aged buildings; that in fact, the Federal Government (then as now) played a vital role in building up the country through things like homesteading and land grants to railroads.

But Walter Knott would have disagreed. The whole idea of the government giving away public land was that it already belonged to the public. And even so, the government made you work for it – and work hard, as the one-time homesteader knew all too well. As for the railroads, these can just as easily be seen as public-private partnerships, developing an asset neither could provide on its own.

Southern California’s Original Theme Park

Ghost Town opened in time for berry season in 1941 and really put Knotts Berry Place on the map. The debate over whether it made Knott’s Berry Farm a theme park really doesn’t apply, as that term didn’t even exist until the late 1950s, after America’s most famous theme park had opened in nearby Anaheim.

The opening of Disneyland in 1955 in many ways only helped Knott’s Berry Farm (as it has been known since 1947). It did force the Knotts to up their game, and add their first real theme park ride in 1960 (the Calico Mountain mine ride, the brainchild of the masterful Bud Hurlbut). On the other hand, over the years Disney has borrowed a few ideas from their older neighbor as well.

For the history of Knott’s Berry Farm as a theme park, you can’t do better than to read Chris Merritt’s delightful illustrated history, Knott’s Preserved (co-written with Eric Lynxwiler).

The Americanization of Walter Knott

Much has been made in recent years about Walter Knott’s political opinions. It’s odd, considering that expect for a stint on the Centralia School Board, he never held public office, never owned a newspaper or a television station, or had a nightly newscast. Perhaps it’s a testament to how successful he was in sharing his beliefs. Or perhaps it’s just that the bigger the target, the more there are certain people eager to throw stones.

Walter Knott’s political opinions grew up gradually over the years. “You’ve got a lot of time to think when you spend all day walking behind a mule,” Marion Knott liked to say of her farmer father. “For many years,” Walter Knott later recalled, “I thought if I ran my business well with good relations with the public and my employees, I would set a good example of American free enterprise, thinking that was all that was necessary. But while I was thinking this our country was going more and more socialistic. Finally I came to my senses and realized that if I and others don’t do something, sooner or later the socialists will be in complete control. Now I devote as much time as I can to try to get the kind of people elected to government that will protect our free enterprise system.” (L.A. Times, 10-30-1960)

Key to Knott’s political views was his belief that free enterprise was the pathway to the American Dream. Thus he resisted the growth of government. “As government expands,” he liked to quote from Thomas Jefferson, “freedom gives way.” For him, patriotism meant embracing America’s ideals and celebrating the nation’s past.

It’s not surprising, then, that the 1960s found him firmly in the conservative Republican camp, supporting Barry Goldwater, Ronald Reagan, and a host of other like-minded candidates. He also helped to fund conservative educational activities, including anti-Communist programs. He also taught himself (by means of Toastmasters International) to become something he was not – a public speaker. He gave his standard stump speech, “Our American Heritage,” scores of times. It was recorded in 1965, and gives a convenient summary of Knott’s ideas and approach. A version of it was also adapted for Helen Kooiman’s 1973 biography, Keeper of the Flame (pp 171-183). (Thanks to Chris Jepsen for a copy of this record.)

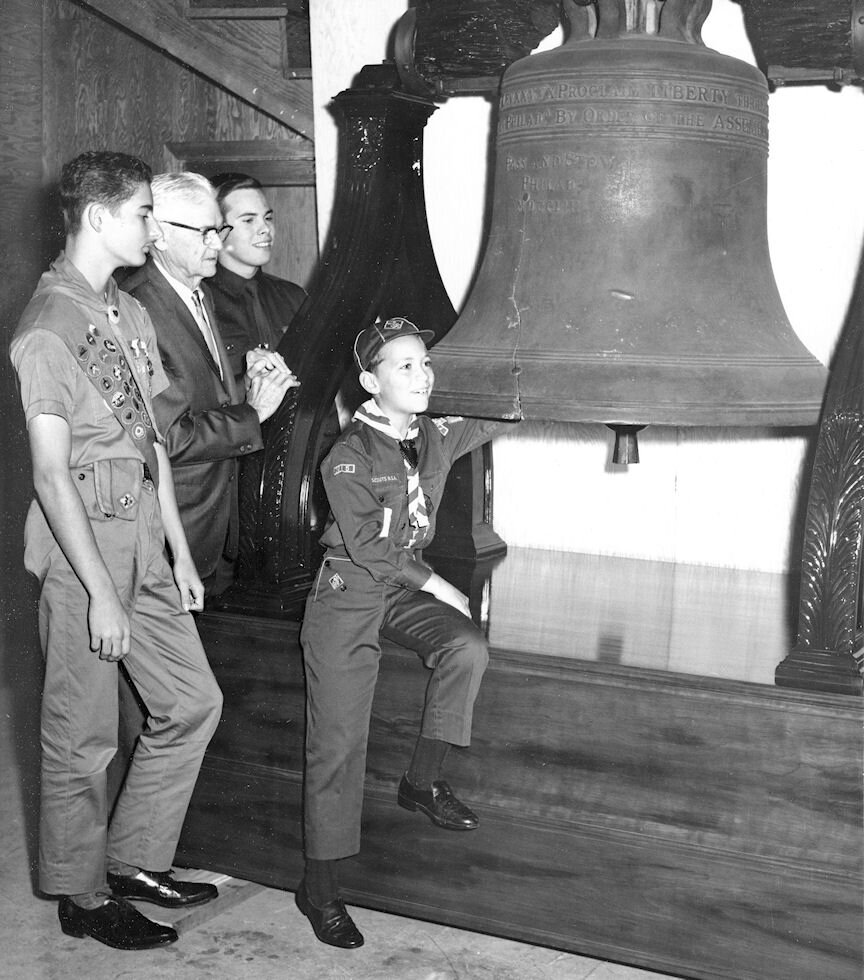

Walter Knott shows off his replica of the Liberty Bell. 1966.

All this brought Walter Knott into conflict with people of other political persuasions. He was often accused of being a member of the John Birch Society. He was not. While he appreciated their strong anti-Communist views, he said he couldn’t support all of their positions. He was certainly an advocate of smaller government, and opposed to the income tax (hardly a unique position in an era when the top tax rate was over 90%). He even refused to cash his social security checks.

“Unlike many on the Far Right, however,” the L.A. Times noted, “– and many on the Far Left as well, for that matter – Knott is not a bitter man. When he speaks of his political enemies … he speaks in tones of regret, not rage – of anguish, not anger.” (2-22-1970)

Some of Knotts’ critics were not so kind. Harold Bienvenu, a professor at Cal State Los Angeles fictionalized and lambasted Knott in his 1964 novel The Patriot, barely disguising his name as Walter Tighe (pronounced “tie” – get it?), and presenting him as a smug, self-righteous fool and a dupe of the John Birch Society (with a lesbian daughter named Cordy to boot). Knott also took a beating in Curt Gentry’s 1968 fictionalized history, The Last Days of the Late, Great State of California.

But Knott’s opposition to big government did not mean opposition to all of its ideas. Starting in the 1940s he offered a profit-sharing plan, and provided health insurance for his employees. He wasn’t against health insurance; he just didn’t think the government had the right to force a business to provide it. Walter Knott believed it was his responsibility to look after his employees. It was just the right thing to do.

It seems to have worked. In fact, when the first attempt to unionize Knott’s Berry Farm’s employees was made shortly before Walter Knott’s death (union organizers called it “one of the most important drives in labor union history” because of Knott’s well-known anti-union views), the employees overwhelmingly voted it down.

Walter Knotts’ celebration of Americanism culminated on July 4, 1966 with the opening of his replica of Independence Hall, where the story of the Declaration of Independence could be told again and again. It was a story believed must be remembered.

In the end, your opinion of Walter Knott’s political activities will probably depend on your own political views. But in any case, your opinion should be based on who Walter Knott actually was, what he thought, and what he did – not just his opponents’ caricature of him.

Cordy’s House

The real “Cordy” Knott continued to work in her tea-room-turned-restaurant for nearly half a century. Walter Knott always gave her a lot of the credit for their success.

Cordelia Knott (courtesy the Orange County Archives).

“My wife has always been a hard working but cautious and practical woman,” he said in later years, “and as such, she acts as a good balance for me. I’m a bit optimistic and impulsive. If a man has a tendency to charge ahead too fast, it does him a whale of a lot of good to have to sell his ideas to his partner and convince her that he can pay for them. I did a better job of outlining and considering my position when I knew I’d have to justify it with my wife. Cordelia and I have always worked as a team; I apply the gas and she applies the brake.”

It was only in the early 1970s, when old age finally caught up with Cordelia that she had to retire.

She didn’t go far. The Knotts were still living in the little house behind the restaurant that Walter Knott had built in 1928. But sadly, after 60 years of marriage, their declining health soon forced them apart. Walter Knott was slipping into Parkinson’s disease, and needed his rooms kept cool; Cordelia needed warmth to be comfortable. In the end, Walter Knott moved to a double-wide mobile home near by, so Cordelia could stay in “her” house for the rest of her life. He was never the same after she died.

Walter Knott died December 3, 1981, just a few days short of his 92nd birthday.

-o-

“What do we mean by freedom? It is simply the right to choose. The right for people to think and choose for themselves. If you lean on government and government makes choices for you, you are most certainly not free.” – Walter Knott