A crew from Anaheim, cementing one of their secondary ditches in 1895 (courtesy the Anaheim Public Library).

Water Wars on the Santa Ana River

Hard to believe today, but the in 1870s armed men patrolled the irrigation ditches in the Santa Ana Canyon and lawsuit after lawsuit dragged on for years, all to procure and protect the water supply for the growing cities downstream.

Anaheim, founded by German immigrants in 1857 as a grape-growing community, had an irrigation ditch on the north side of the river from its earliest days. The Yorbas, on Bernardo Yorba’s old Rancho Cañon de Santa Ana, had been irrigating since the 1830s, and in the 1870s, the ranchers in the Placentia area had built their own series of flumes and ditches, known as the Cajon canal.

On the south side of the Santa Ana River, the Yorbas, Peraltas, and their tenants and kin had been digging irrigation ditches since the 1810s. They were followed by the first American settlers in the 1860s and ‘70s who relied on the water to fuel the growing towns of Orange, Santa Ana, and Tustin.

In 1871, Alfred Chapman and his partners (the founders of Orange) completed a major irrigation ditch to the new townsite. In 1873 they incorporated as the Semi-Tropic Water Company and the water system was extended south to Santa Ana and Tustin. The Germans in Anaheim were concerned, but made few complaints. Soon Riverside and other upstream irrigators were also pulling water from the river, yet the stream still flowed.

A map of the waterworks on the Santa Ana River from Corona to Anaheim as they existed in 1908 (Santa Ana Register, October 5, 1908).

But 1877 was a dry year, and by early summer Anaheim was a trouble. The mouth of their ditch lay downstream from the Semi-Tropic headgate, with a mile or more of sandy streambed and boggy stretches in between. They simply weren’t getting enough water. Worse, the Semi-Tropic had built a low earth and brush dam across the river, forcing (said Anaheim) more than their fair share of water into the Semi-Tropic ditch.

The Semi-Tropic insisted that, as always, they were only taking half. They even offered to carry water for Anaheim through of their ditch before releasing it back into the riverbed, avoiding some of the porous, sandy stretches. But Anaheim would have none of it. They firmly believed that they had the right to as much water as they could take.

It all came to a head in June 1877 when the Semi-Tropic’s men “wrongfully, unlawfully, and with force of arms” diverted – almost all the water (said Anaheim) – only half (as usual) said the south side. “At that time…,” Director F.A. Korn of the Anaheim Water Company later testified, “the Semi-Tropic Co. claimed one-half of the water that was in the river, but they had taken out three-fourths. They filled their ditch and didn’t give a straw.”

Facing off in the canyon were the Zanjeros for both companies -- Henry Knapke of Anaheim and Fred C. Hazen of the Semi-Tropic. (American settlers in Southern California had adopted a number of Spanish water words, including zanjero for ditch-tender and toma for diversion dam.)

Both men were large, fearless, and well-armed. John Fischer of Anaheim recalled that Hazen carried both a pistol and a bowie knife, “and always was there with a shotgun at his back.” “He was a pretty good sized boy. I did not like to fight with him. He was about 20 years of age and he said that he would defend the water and the ditch and keep the water in the ditch in spite of the damned Dutchmen.” (That is, the Germans – from Deutschland – a common 19th century epithet.)

Called to the witness stand four years later, Hazen was unrepentant: “I always carry arms for reasons I consider justifiable,” he said firmly.

“I remember seeing Mr. Fischer and others from Anaheim inquiring about the water. They frequently came up there. I don’t know whether I had a pistol or a bowie knife on at that time. I sometimes have them and am wearing them now. I didn’t draw on any men to my knowledge.”

Amazingly, Hazen was actually armed in court.

“The knife which I now have on my person is the same one I think which I had at the time of the difficulty with Knapke in the summer of 1877,” he testified.

“How long is that knife?” one of the Anaheim attorneys asked him.

“I don’t know,” he answered. “So long that it would take a Dutchman like that (showing)…. I can handle a Dutchman … very well. They don’t seem to have any fight in them.”

Perhaps realizing that he had been bragging a little too much, Hazen quickly added: “I had no idea of handling any Dutchman. I used that expression. Don’t suppose I ought to.”

Knapke, he claimed, had a crew at the head of the Semi-Tropic ditch, cutting away the earth and brush toma, “and letting out the water, and he sent a very insulting message to me … that he had arms, and that he would like to see the son-of-a-bitch come up there and regulate the water while he was around.”

“That is a message which I don’t want to take from a fellow seven feet high. I thought [that if] I would go up and regulate the water if Mr. Knapke was there next time I would have a good chance. The message did not make me so angry that I killed any one. I went with a level head. They also said that he had arms, but did not state what.” Nonetheless, Hazen and his men went up and rebuilt the dam.

When he and Knapke met a few days later, “Says I: Mr. Knapke, you take that turf out and I will put you in the place of it. He said that he could take me with one hand and stick my head in the water. I told him he was big enough to do it but I did not believe he would. We talked there for an hour.”

Hazen continued to guard the Semi-Tropic ditch, sometimes sleeping near the headgate at night. “One day the whole [Anaheim] Board of Directors came up,” he testified; “cut off some forty feet [of the toma]; pulled up the stakes and the brush, and in the worst places they could find, and let out all the water. That is one time they got water in Anaheim. At another occasion the ditch broke and there were shovel marks on the bank. That was twice they got water in the dry time.”

The Anaheim Water Company sent the directors of the Semi-Tropic an ultimatum – release the water or we will sue. The Semi-Tropic insisted they were only taking their fair share.

The lawsuit that followed became the most famous (and the longest) of the many lawsuits over the waters of the Santa Ana River. Though filed as the Anaheim Water Co. et al. vs the Semi-Tropic Water Co. et al., the defendants actually changed along the way. Just weeks after the lawsuit began in 1877, the ranchers in Orange, Santa Ana, and Tustin bought out the Semi-Tropic and formed their own joint stock company – the Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company. They bought the entire water system and inherited the lawsuit.

The “et al.” defendants were mostly Yorbas, and a few other upstream irrigators on the north side. This was odd in a way, as Anaheim always claimed their water rights descended from the Yorba family rights – which they were now questioning. In any case, the judge eventually dismissed the case against the Yorbas, et al.

The Anaheim case also carefully avoided any mention of Riverside and the other upstream water users. This would be purely a local fight.

Even as the attorneys fought it out in court, conflict continued up the canyon. In the summer of 1879 the Anaheim Water Company put their own dam across the river, diverting all the water to their side. The SAVI secured a court order to have it removed and immediately, “a number of our citizens repaired promptly to the spot, equipped with shovels and necessary tools, and demolished the offending dam,” wrote Orange’s correspondent to the Anaheim Gazette (June 7, 1879). “There is but one feeling among the stockholders of the Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Co. in regard to this transaction, which is that it was a fiendish outrage upon their unquestioned legal rights, and one deserving the severest punishment…. The transaction was an unfortunate one, as many suits for damages are likely to be brought, and more or less bad blood stirred up between the two sections.”

Henri F. Gardner, who worked as a zanjero for the SAVI in the 1870s, later recalled that during the long trial, the water was “adjusted by shot-gun law; that is, we – the people on the south side – took our half and guarded the dam while Anaheim cut the dam as opportunity served. There were personal collisions between the ditch men, but luckily – and I often wonder how it happened – no lives were lost. This method continued, even after the decision and during the new trial and appeal proceedings, to 1883 and later.” (Santa Ana Register, September 28, 1908)

More than once, the south side irrigators offered to compromise, and formalize a 50/50 split of the water. In 1882 the Anaheim Gazette reported that the SAVI was ready to offer $5,000 if Anaheim would dismiss all the lawsuits and acknowledge their right to one-half the flow of the river. The Gazette (November 4, 1882) replied that while there were many Anaheim Water Company stockholders who favored compromise, they would never settle for such a “paltry sum.” “There is not an Esau among them.”

Though filed with the Los Angeles County Superior Court in 1877, the case “dragged along with demurrers, amended complaints, etc.” until 1881, when it finally came to trial. No local judge felt qualified to hear the case, so Judge W.T. McNealy came up from San Diego to hear testimony. There was no jury.

Each side presented both legal and historical arguments. The Anaheimers relied on the principle of “appropriation,” which held that the first irrigator to divert water from a given stream had rights over any other later users. The south side ranchers relied on the principle of “riparian” rights, which held that every property owner along a stream had a right to a share of its waters, whether they used them or not.

Historically, Anaheim pointed out that at the time of its founding in 1857, they had not only bought 1,165 acres in the Rancho San Juan Cajon de Santa Ana from Juan Pacifico Ontiveros, but also purchased a right-of-way for an irrigation ditch from Bernardo Yorba across his Rancho Cañon de Santa Ana upstream. They began using water from the Santa Ana River in 1858, and a year later formed the Anaheim Water Company to operate and develop their irrigation system.

The Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company replied that its stockholders’ rights came from owning portions of the old Rancho Santiago de Santa Ana, giving them a riparian right to half the water. But if the question was early appropriation, they could show that the rancheros on the side of the river had been taking out water through various ditches since the 1830s, if not before. And to prove it, they called some of the oldest members of the Yorba and Peralta families as witnesses.

Rafael Peralta (1816-1894), a son of Juan Pablo Peralta, who shared the grant of the Rancho Santiago de Santa with his uncle, José Antonio Yorba, recalled that, “I knew José, Tomas and Teodocio Yorba [the sons] in 1835. They lived near where Orange now is. Tomas used to have a vineyard and used to occupy himself in taking care of it and his crops and his vaqueros used to look after his stock. He cultivated and irrigated corn, beans and wheat. He had a great many servants and cultivated a good deal…. José Yorba cultivated land in 1835 to a considerable extent. He had a large number of servants employed. The land so cultivated was west of Orange…. He raised there corn, wheat, watermelons, pumpkins and a small variety of beans. He had a great number of servants employed aiding in the cultivation. Teodocio Yorba also cultivated land in 1835….They all raised about the same sort of crops and irrigated from the river.”

José Dolores Sepulveda (1826-1905), a brother-in-law of Tomas Yorba, lived with him from about 1835 to 1843. “I don’t know the acreage contained in the tract which Tomas Yorba cultivated in 1835,” he testified. “In those times we knew nothing about acres, but it is my opinion that he cultivated about one hundred and fifty acres and more…. In 1841 the field cultivated there was very large. From the rancho of Tomas to where José Antonio [II] lived was about three miles, and [it] was all cultivated in 1841. They cultivated all that plain south of Teodocio Yorba – all along the edge of the river for more than two miles…. There was a great deal more land cultivated in 1841 there when Don Tomas was alive than in 1850.”

Under cross-examination he added:

“Don Tomas was a very energetic man – there was not a man in the country like him. He died in 1845, and when he died this industry did not continue as it had been during his lifetime. I left here in the year 1848 and a great many people left with me at the time of the gold excitement. There was not as much land cultivated after this. A great many people left and the price of cattle went up. The rancheros did not cultivate as much land in these years because the price of cattle was very high.”

While not as brash as Fred Hazen, some of the Mexican witnesses also grew weary of Anaheim’s cross-examination. Pío Quinto Davila, who had come to teach school on Bernardo Yorba’s ranch in 1858, was asked repeatedly to estimate the size of the irrigation ditches then. They “were of sufficient capacity to have bathed a lawyer,” he answered more than once.

Judge McNealy weighed all this testimony, and the documentary evidence, and in March 1882 issued his ruling. Standing on the notion of appropriation, he sided with Anaheim, ruling that they had the right to ‘a full ditch.’ But in a second ruling, in a related case, he also held that Anaheim could not interfere with the SAVI’s right to half the water in the river.

“The decision is sweeping and grants everything asked by the plaintiffs,” wrote a correspondent from Anaheim. “There is great rejoicing here, as the amount of water is sufficient for the needs of this entire country, and this section will now go rapidly forward. This decision maintains the doctrine of prior appropriation, and is in keeping with other decisions lately rendered in other counties. The magnitude of the interests involved make the case one of the most important ever tried in this or any other county.” (Los Angeles Times, April 14, 1882)

The defendants on the south side of the river seized on the obvious conflict between the two decisions: “In effect the learned Judge decided that the Santa Ana Co. shall have one-half of the water, and then again that it shall not. But this is a ‘decision which has not been decided.’ The Santa Ana Irrigation Co. will apply for a new trial, and if denied appeal to the Supreme Court, which will undoubtedly set aside this ‘decision which was NOT decided.’” (Santa Ana Herald, April 8, 1882)

Denied a new trial, the Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company appealed to the California State Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court made quicker work of the case, issuing their ruling in September 1883. Legally, they upheld riparian rights (still an important standard in California law). Historically, they pointed out that the 1857 right-of-way deed from Bernardo Yorba said nothing about water rights, and only gave permission to dig a ditch. The Ontiveros deed for the townsite did give them certain water rights (as his rancho was also riparian to the river), but not the right to sell irrigation water outside the original 1,165 acres. Finally, if prior appropriation was at stake, the court agreed that the owners of the Rancho Santiago de Santa Ana had been irrigating long before Anaheim. The original ruling was overturned; Anaheim had lost.

But the judges had a final word for both sides: “[W]e think it not improper to suggest, in view of the value of the water in dispute and the large interests at stake, whether it is not advisable for the parties to the controversy to divide the water upon an equitable basis, and devote the money that may otherwise be expended in litigation in the proper development and judicious use of it.” (64 Cal 185)

Finally Anaheim got the hint. Neither lawsuits nor ‘shotgun law’ were going to keep their ditches full. It was time to compromise.

The SAVI had already moved their intake further up the canyon, almost to the county line, to Bedrock Crossing, where rock formations forced most of the flow of the river to the surface. There the two sides agreed to make their 50/50 split.

Rather than extend their old ditch, the Anaheim Water Company bought out the Cajon Irrigation Company, which in 1878 had completed an elaborate system of ditches and flumes to bring water to the Placentia area. In fact, Anaheim went right on buying out the other north side irrigation companies and combined them in 1884 into the Anaheim Union Water Company.

Tensions remained between the AUWC and the SAVI (the 1884 split was not completely formalized until 1899), but they could at least agree on some common goals. They joined together in several lawsuits against Riverside, and jointly purchased land in the Santa Ana Canyon both to secure water rights and build their own water systems. The Anaheim system was sold to the City of Anaheim in 1967. The Santa Ana Valley Irrigation Company turned off the water in 1974.

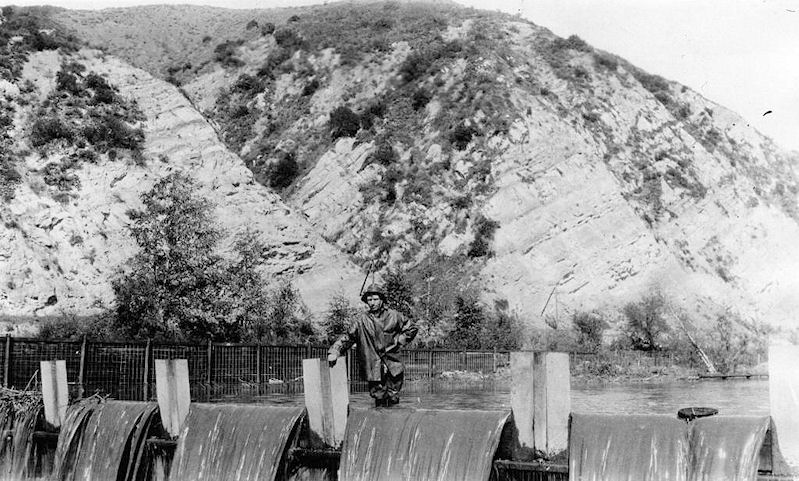

An early division gate in the Santa Ana Canyon (courtesy the Anaheim Public Library).